Mallards (MALL)

Introduction

A Tale of Two Worlds

Spanning locales from the serene waters of New Zealand to the vibrant habitats of Hawaii, the Mallard has truly global reach. Yet, there’s a twist in its tale that dates to 1650. King Charles II of England, noticing a decline in local duck populations and an enthusiast of hunting, began a pioneering effort in domestic breeding. These early domestic endeavors laid the foundation for Mallards that have become domesticated over time.

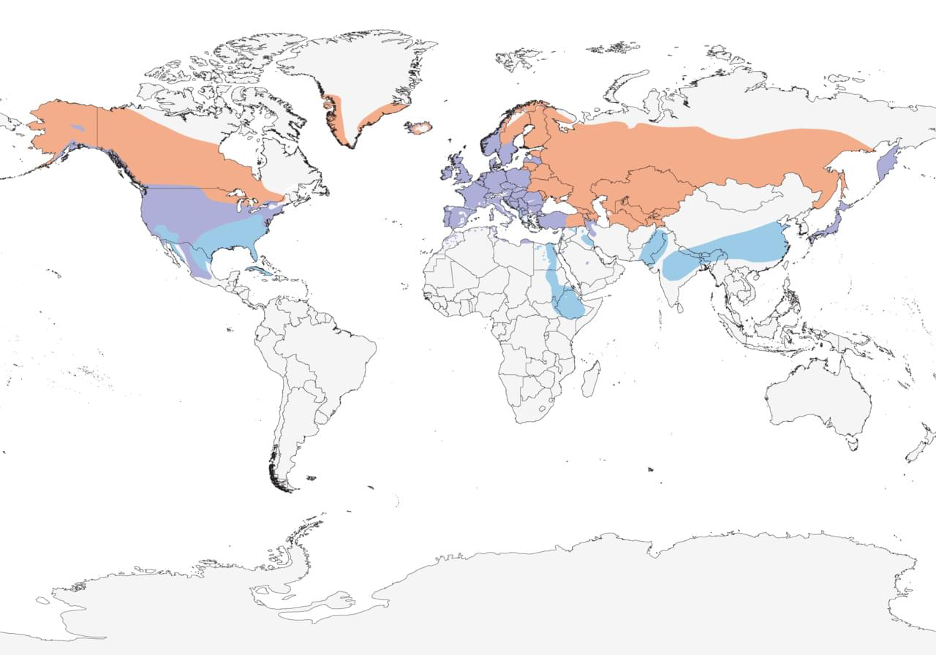

As one moves deeper into the world of this species, a genetic tapestry unfurls. European and Eurasian Mallards, termed “Old World,” display a unique DNA sequence distinct from North American or “New World” Mallards. The 1920s saw Europe mastering the breeding of the game farm subset. These domesticated birds, when introduced to America, began to mingle, and mate with the wild American breeds. This melding of lineages resulted in altered genetic sequences with distinct characteristics. For instance, farm-influenced Mallards exhibit reduced migratory instincts often remaining local year-round. This diminishes their offspring’s likelihood of embarking on, or successfully completing, migrations. Furthermore, their ability to forage naturally in the wild, a survival trait, is notably compromised.

This genetic infusion, while fascinating, has had significant repercussions. The period between the 1920s and 1960s witnessed the introduction of approximately 500,000 game birds, predominantly of Old-World genetics, into the eastern flyway each year. This number has tapered to about 150,000 over the past five decades. As a result, the hybridization has inadvertently weakened the wild Mallard’s proficiency to thrive in natural habitats. The offspring, borne out of unions between domesticated and wild Mallards, often lack key evolutionary traits, jeopardizing their long-term survival in the wild. Researchers indicate that if one were to randomly select a Mallard from the wild in the Great Lakes region, there is only a 2% likelihood that the bird possesses entirely wild genetics.

Yet, beyond this genetic narrative, this species exhibits a range of intriguing behaviors and attributes. Their feeding habits are versatile, dabbling in water and foraging on land, consuming a diet from plant material to small aquatic animals. When it comes to nesting, pairs form in the fall and winter. Their courtship displays are quite a spectacle, with males engaging in a range of actions from dipping their bills in water to vigorous vocalizations. Females, once they’ve chosen their nesting site, lay around 7-10 eggs, incubating them for almost a month. Post-hatching, ducklings are immediately led to water and, while tended by the mother, they’re largely independent feeders.